How we view our history and future can be skewed, or even screwed if we don't see either well. I promised my readers I would…

“The Passion of the Christ” Confounds Compassion with Cruelty

[Intro to this post.] Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” is offensive.

It starts dreary and goes gory. The brave honesty and loving kindness of Jesus is absent. Undeserved agony is the only story. Then, in the end, poof! He’s all cleaned up and fresh again, miraculously.

It offends as Christianity does, making Jesus fit its scheme: An inscrutable God sends his own son to suffer and die for the sins we do in order to save us from the even more hideous hell He supposedly intends for those who won’t believe in this preposterous plan.

Instead of critiquing this, the controversy is whether the Jews look bad, having “killed Christ,” even though Jesus and his guys were Jews too. Jews should be neither guilty nor proud. Should we be mad at Italians now because Romans whipped Jesus then? Absurd. What should rouse our ire now is cruelty on any innocent. Denying another his or her right to life, torturing and killing anyone (not just one divine one) – these are offenses our enlightened humanistic democracies have mostly risen above.

That parents would shriek at children glimpsing a distant breast, yet send their innocents to see Gibson’s horrid spectacle, makes me grieve and worry for the spiritual health of our country. That people would flock to this but avoid the far more important (and violent) “Fog of War” shows a fascination with violence without responsibility for it. Jesus was one of thousands so-killed. Last century we burned to death hundreds of thousands. That we recently invaded those who never attacked us, looking for weapons only we had, and plan more wars, makes me wonder if our largely Christian culture emulates the one who said “love thy neighbor” or those who staked him.

[Start of original sermon, “Passion’s Fog”]

Passion can fog the mind. We can get so roused or riled we no longer think clear or heed our conscience. We can get so swept up in lust, love or anger we think of nothing else. We can get so full of zeal we barely notice or care what it does to others. I’m not against passion. We need passion to enliven us. Like Rod Stewart’s song says, “Even the president needs some passion, passion.” The mild twinges of passion we get from watching movies or the TV is a faint touch of the powerful feelings we may need from time to time just to keep our systems in dynamic hormonal balance. TV and movies are the modern version of story telling and hearing, bringing us fear, anger, revulsion, excitement, arousal, resolve, and so forth. We need passion, but we know it can fog our mind.

That’s why I’m so concerned about the twisted values and lessons coming out of this Easter season’s popular movie, Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ.” Gibson stands to make some seven hundred million dollars – so popular is this feast of cruelty. Millions will look to it for lessons in spirituality. Busloads of children will be shown this horrid spectacle and be told it is for “fixing their sins” that this happened. Many say this creates faith; I say it creates fog.

I pause before saying why to also say I like most Christians just fine. They tend to be decent people in general. Some who claim to be saved – seem so. Their lives get fixed up and their spirit is bright. I value the decent values Christianity has established in our culture, values I share, like compassion, kindness, and truth speaking.

I was raised up a Catholic Christian, but left that religion at age 15. Though I have also come to appreciate Eastern religious perspectives and practices, admire Humanist thought, and have gladly been a Unitarian Universalist minister for thirty years, I have gratitude for much of Christianity’s influence in me and our culture. But because I’ve always been somewhat of an independent thinker, and have had the unusual luxury of being supported and encouraged to think and speak freely in a liberal religious setting, I have also developed, not just skepticism, but criticism of some aspects of Christianity. These are exemplified in Gibson’s movie and the meaning it is supposed to have.

I can’t recommend you see it. It’s a dreary degrading film, a descent into unremitting cruelty and gore galore. It is the twelve Stations of the Cross pushed in your face via cinematic excess. Those seeing it are being advised of the real message – Jesus died for our sins. Both the movie and the meaning offend.

I can recommend “The Fog of War,” an extended interview with Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense during Vietnam, illustrated with photos and movies of our various wars last century. McNamara provides a great service to our world by facing the hard trials of statecraft and the horrid facts of war. All who think we should wage war, and all who think we shouldn’t, should see this important and alarming movie.

I’d like to put the two movies together on this Palm Sunday in an effort to help your Easter this spring be more about rebirth than re-death. To do this I will look at the violence depicted in the two movies in order to look past it to the goodness and glory in life and us.

No doubt, violence and suffering are a part of life. All experience both, though some are steeped in them. Religions can offer solace for suffering, or sanction inflicting it. Religions can scorn violence, or summon it. Though the world’s great religious teachers have been profoundly kind, the religions that they inspired have sometimes not. Early Christianity practiced radical kindness. The apostles and saints accepted death rather than inflict it. Some of the religions it supplanted were horribly cruel. Christian monks, nuns, and hospitals brought great peace, solace, and healing to civilization. The early symbol of Christianity was the fish – sign of unexpected, unearned abundance.

Latter Christianity often lost this. The central symbol became the cross – sign of undeserved, unjust suffering. By centering on this, all the truthfulness, inclusiveness, and kindness of Jesus get lost in a story that needs a victim and a victimizer. To put on The Passion Play both a Jesus and a Roman soldier are needed. Yes, the saints were martyred, but yes, so were many innocents in the Inquisition, Crusades, and Holy Wars. Somehow, having that central symbol calls forth quasi crucifixions. I call it “the shadow of the cross.”

The controversies that surround Gibson’s movie miss the point. We hear the controversy is whether the Jews look bad, having “killed Christ,” even though Jesus and his guys were Jews too. Jews now should be neither guilty nor proud of what Jews did then. Should we be mad at Italians now because Romans whipped Jesus then? Absurd.

What should rouse our ire now is cruelty on any innocent. Righteous indignation grown to murderous arrogance is wrong whenever it occurs by whoever commits it. Denying another his or her right to life, torturing and killing anyone (not just one divine one) – these are offenses our enlightened humanistic democracies have mostly risen above. We are rightly repulsed at terrorist murders. Even if the cause seemed sensible or the doing of it brave, we cannot condone the killing of those who did no wrong, of those who just happened to be in a hated category.

We were shocked and offended to the core when Saudi Arabian Islamic zealots murdered almost three thousand innocent people on 9-11. But were we shocked and offended at the thousands of innocent people we then killed in sloppy retaliation? When we grieve for our boys being killed in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan do we also grieve for their boys, or girls, or parents, or culture? No, our limits of concern tend to go only to us and ours, not they and theirs. American regret for Vietnam tends to go only to the horrid fifty seven thousand Americans killed, not the all the more horrid million more people who were also killed.

It’s ironic that our largely Christian culture should so easily slip into murderous violence on innocents when the person who Christianity supposedly centers on was so kind. He expressly taught, “Love thy neighbor,” and “turn the other cheek.” When asked how many times we should turn the other cheek, he replied, “seventy times seven.”

When we lashed out in fear and revenge after 9-11 we didn’t even target the right people. We hurried to invade those who never attacked us, looking for weapons only we had, threatened nuclear reprisals, and announced plans for more wars elsewhere. Our largely Christian culture is largely proud of this, flapping flags in approval.

I don’t think Christians are conscious of the cruelty they condone. They flock to see “The Passion of the Christ” and watch poor Jesus get shredded and spiked but don’t go beyond fascination with violence to renunciation of it, putting us in a dangerous fog. It wasn’t Jesus who created the fog but those who came after, from Paul to today’s TV preachers. They impose a bizarre scheme on poor Jesus: An inscrutable God sends his own son to suffer and die for the sins we do in order to save us from the even more hideous hell He supposedly intends for those who won’t believe in this preposterous plan.

I know criticizing this seems offensive to those who hold this belief dear. Despite my objection, many find solace and spirituality in this widespread belief. But I am of the Unitarian tradition, which has never accepted the theological but non-scriptural trinity and sees Jesus as he saw himself – praying to God, not playing God. I am also of the Universalist tradition, which has long objected to the whole human notion of hell and instead finds scriptural and intuitive reason for a loving God – rather than an inscrutable and mean one. And I am of the Humanist tradition, which values all human beings, not just one divine one.

I agree with God, when in Genesis One S’he declares energy, matter, plants, animals, and humans – males and females – to be “good.” I know we don’t always live up to our goodness, but I don’t believe in any inherent fallen nature or inherited Original Sin, as is supposed from Genesis Two and Three. Looking for the bad in us is a self-fulfilling, self-justifying, and self-perpetuating philosophy and psychology. It seems to lead to a faith so devoid of ethics, the more fallen we get, the more saved we feel.

This twist can lead to twisted results. That parents would shriek at children glimpsing Janet Jackson’s distant breast, yet send them to see Gibson’s horrid spectacle, makes me grieve and worry for the spiritual health of our country. What are the children to think of the guilt-inducing trick: that they are responsible for his agony, but ultimately that’s OK? That people would flock to this but avoid the far more important (and violent) “Fog of War” shows a fascination with violence without responsibility for it.

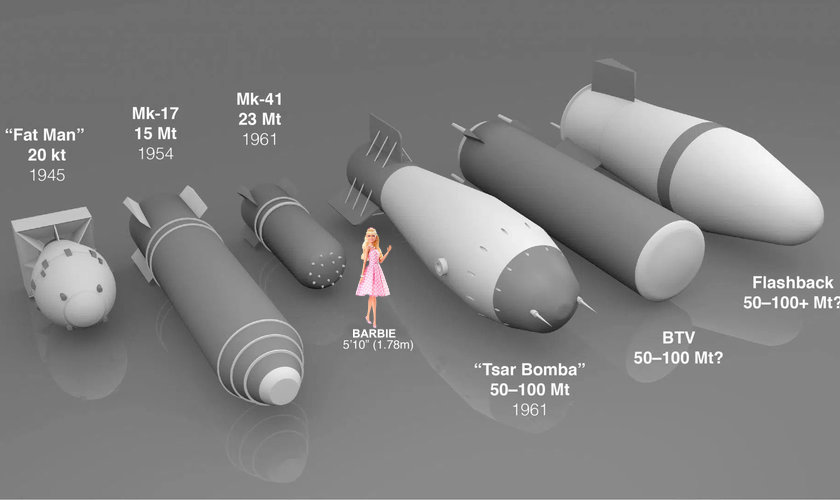

Jesus was one of thousands so-killed. Last century we burned Japanese civilians to death by the hundreds of thousands, killing over half the residents in two thirds of their cities. That we recently invaded Iraq, who never attacked us, looking for weapons only we had, and plan more wars, makes me wonder if our largely Christian culture emulates the one who said “love thy neighbor” or unconsciously acts like those who staked him.

I would ask Christians who might read or see this to consider the paradox and irony of their picking Jesus but then not trying to act as humanely as he did. I would further ask that they find and watch “Fog of War” and consider seriously McNamara’s important issue: that we have not grappled with the rules of war, nor have we asked ourselves if we want to bring the incredibly violent scope of war from the 20th century into the 21st. The unjust torture inflicted on Jesus, horrid and reprehensible as it was, was personal and limited. The unjust agony inflicted on civilian populations (as well as the soldiers themselves) in last century’s wars magnifies Jesus’ agony by the millions.

Would we rationalize that away or simply turn the other way? Would we not care that it goes on – and that our recently announced plans are for it to go on and on – unless it’s our buildings that fall? Would we protect ourselves from seeing the flag-draped coffins of our boys returning home to their graves in order to not realize what we’re doing?

Americans probably don’t even know and perhaps wish to forget our horrendous firebombing of Japanese cities prior to using atomic bombs on them, deliberately napalming to death most of the residents of most of their cities. Some Americans say “better them than us,” thinking attacking the civilian population is a legitimate tactic of war. But, if fair on them, then fair on us. If we don’t live up to the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” we tend to promote its shadow, “As ye do unto others so will it be done unto you.”

The wife of Norman Morrison, Quaker peace protestor who immolated himself on Pentagon steps, said this: “Human beings must stop killing other human beings.”

McNamara, aware of the violence from “the war to end all wars” to our current one, representative of all of us, could not explain the shallow rationales and egregious results of war; all he could do was to say it gets out of hand, that it becomes the “fog of war.”

We know that all human beings are built of a selection process that would kill rather than be killed. Usually, people are peaceful, but provoked, most humans can become killers. We know also that in most societies the aggressive warrior and the bossy religious zealot periodically want to take over and make everyone play their games.

It might be that those in fundamentalist-dominated Islamic societies are stuck with their religion and their religious nuts, but we don’t have to be in ours, though we increasingly are. Bizarre preachers dominate Sunday morning TV and most religious radio with far-fetched scenarios drawn from disparate Bible passages and their own flamboyant imaginations, praising the passion movie and foretelling the grand final conflagration that will bring the “Prince of Peace” back. What used to be innocuous whackos have become influential ones, buoyed by a society of nodding agreers, advising a sanctimonious president [G.W. Bush], urging our country be “under God.”

Kind-hearted Christians don’t seem to have much say or sway these days. Nor do secular Americans. Believing matters more than doing. Faith trumps rationality. Piety parades. What in the name of Christ has Christianity become?

“Christ” was not Jesus’ last name. It was a title applied later, an interpretation of various scripture passages and that event. Does believing we are fallen but are redeemed by Jesus make us good without our having to be good? I know many report they want to be good because they have faith. I believe them. But isn’t being a Christian more than having faith? Or is faith itself enough no matter what we do? Can we wage wars and still feel sanctimonious if we just believe in the scheme Paul and others made up and the lies our president told us?

I’m with Thomas Jefferson in being wary of religion. Religions are not above human reproach. Religions aren’t made good and right just because they claim to be. We need to be both heart-full and intelligent about religion. Jefferson took his scissors to the Bible, cutting out all the added miracle stories and commentary about Jesus, paring it down to the sayings of Jesus.

Even though I criticize some aspects of Christianity, I like others and I like Christians. On balance, I’m glad our western civilization has picked Jesus as teacher and inspiration. Jesus was not one to engage in gruesome violence or wage wars. He seemed to care for people in and of themselves, not because they were in some despised category. He reached out to the poor, the prostitute, and the tax collector. He even was said to have said, “in the least of these, there you will find me also.”

This is not different from one way to understand the meaning of YHWH: I am that I am. God is the self of the one you look at. God is the self of the insignificant foreigner, even the enemy. (Even if we don’t love our enemies, respecting them goes a long way to mend the divide.) Theologians, mullahs, or preachers do not own or limit God. Emerson called it a perversion “that the divine nature is attributed to one or two persons, and denied to all the rest, and denied with fury.” Death is not escaped by believing in the cross.

Must those who see the crucifixion as the good thing define Christianity? Our passion should be to abhor any crucifixion of any one. Adding more crosses to the modern Apian Way makes us neither powerful nor righteous.

What a different world there could be if Christianity were to drop the whole rush to idolize execution and create Armageddon, drop it for the madness it is and instead see the Second Coming as the knowing of God in all. Seeing divinity (or at least worth) in “the least of these” could open the collective floodgates of love that would pour forth into humanity and its future unexpected abundance and miraculous community. Of late, it appears liberal Christians, non-theistic religions like Buddhism, and humanistic secular people are doing better at this than the three fanatical monotheistic religions are.

We need to drop wrath and return to the goods of God as defined in Genesis One. We need rebirth, not re-death. As there are more trout in the streams, more security and sustenance for the human family, more freedom for all, and more joy in our hearts – so will the fog of our misplaced passions dissipate in the warm glow of our singular sun. Passion’s fog will burn off by our being more honest and loving in our lives – like Jesus was in his.

Reverend Brad Carrier, for the Unitarian Universalist’s of Grants Pass, April 4, 2004, C

Subscribe

0 Comments