How we view our history and future can be skewed, or even screwed if we don't see either well. I promised my readers I would…

The Purpose of Life is to Give Life Purpose

When I met Shri Bhagwan Rajneesh in a posh hotel in Bombay I wanted to punch him in the nose. I had gone to India sick of the west’s view of earth as merely a place for a divine drama that leads to an afterlife. In India I found its counterpart: a yearning for an instead-of life. Rajneesh sported a Rolex as he knocked the communists for wanting worldly improvements. He assured us the body isn’t real and neither is this world; they’re merely maya, illusion compared to the Self. So I wanted to punch him in the nose, pull back my fist, and ask him a philosophical question: “If we aren’t the body, would you mind if I punch you again?”

Actually, I admire Rajneesh and didn’t want to hurt him. Nor do I want to hurt those in the west who think our world is a mere stepping stone to heaven or hell. I just want religion to care for the physical base that allows us to be at all. If religion is that which relates us back to the reality we’re estranged from, then I’d like us to love life, our obviously important base of existence. Too much, we toy with it as if it didn’t matter.

A counterpart to the eastern view exists in the west: that we are the center of a divine drama. God above presents us with a temporary test on earth’s stage to determine our eternal fate. Earth itself had no divine importance. The animals and plants, the ecology of interrelated systems, all served this great test. A caring or wrathful God hovered just above, watching our every move, judging us against a set of firm and stern rules. The first humans, Adam and Eve, only a few thousand years ago broke an early rule, just as we have broken subsequent ones. The whole purpose of life was to make amends, believe in God, and get saved from the fires of hell we otherwise would inherit. We do this, not by living ethically, but by believing in the whole far-fetched scenario they present. We’re religiously good if we live by faith, no matter what that means to our world.

Take the prevailing Christian stance towards science and evolution. Since before the Scopes monkey trial, evolution was seen as a threat to a religious sense of our human importance and purpose. Evolution theory took no care to play this religious game. It related us not only to apes, but to pre-ape animals, back through a fantastically magnified scale of time through early life forms to mere happenstance chemistry in a vast and indifferent universe.

God wasn’t needed in this view, which offended those who believed in Him. They reacted angrily to losing their purpose, their God, and their comforting scales of size and time. They assumed if God isn’t in the picture and we don’t have to obey His commands, what would we do? Would we descend into chaos and anarchy, go about having orgies of sex and violence? If the old rules are off, what are the new ones?

I have some sympathy for this fright and question. Take away that authority, then why live one way or another? Maybe they’d be just as bad as they imagine others are or that they might wish to be.

Recently, the fight against evolution theory has taken on a new name. Instead of Creationism, Intelligent Design postulates that nature is so complex and amazing it can’t have “just happened,” and therefore was created by some super-intelligent being. Though not named for fear of being rejected on separation of church and state grounds, they really mean God.

I have some sympathy for Intelligent Design for two reasons: One, it shows some rudimentary awareness of the scientific process (even though it also refuses to come up with a testable hypothesis and doesn’t engage in peer review). Two, it begins to expand the simplistic religious view of how we got here and why to include bits of the overwhelming complexity and majesty of natural existence.

Complexity doesn’t prove design, as theologian William Paley argued in 1802, but it does exist in unending splendor. The awe of the psalmist for the miracles of life and the mystery of the starry heavens has suddenly been magnified exponentially by virtue of the scientific method. We know a lot more about our home than we ever did before, but we also know we don’t know even more. As knowledge expands, so do questions. Saying “God only knows” staves off our uneasy ignorance, but it also subverts our ever finding out the facts.

By putting the God-answer in the classroom and statehouse we undermine our chances of meeting the demands of modernity. Can we face up to the reality that makes us up without succumbing to a devilish nihilism? Can life as we know it still have purpose?

What if there is no external meaning supplied? What if we are made entirely of happenstance, physical forces creating chemicals which tend to coalesce into replicating forms that assemble into increasingly complex organisms? What if we’re related not only to apes, but to other mammals, birds, lizards, worms and primitive plants? What if the blind forces of natural existence have given rise, not only to interrelated life systems, but conscious life capable of weighing the outmost stars and the inmost particles? What if we took this inheritance with astonished gratitude and creative care?

Our own Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his infamous and prophetic “Divinity School Address” of 1838, complained the church dwells “with noxious exaggeration about the person of Jesus.” He railed against the false impression of “Miracle” of the church. He called it “Monster,” for not being “one with the blowing clover and the falling rain.”

Simple clover is an astonishing confluence of structure and function, changing sunlight into shape, living and growing, giving birth to itself even as it gives oxygen and compost to life.

The water that falls as rain is three thousand seven hundred million years old. Those hydrogen and oxygen atoms started humming as discrete items that long ago and have gone through all the states of being liquid, gaseous, and solid since. They have been through it all: the movement of continents, the rise and fall of various forms of life, the rising and falling of evaporation and condensation, the stuff of cells and blood, the cleanser of earth’s body and ours. The life-giving water in your body is that old. It serves you now, and it will go on serving after it leaves you.

Modernity beholds a universe so astounding as to frighten us. At the same time, it is a knowable and a reliable universe. The laws of physics and chemistry that prevail here apply there. Such laws are the gateway to freedom. Gravity may hold us on the ground, but it also creates the air pressure that varies with the shape of a wing flying through it, providing relative lift. By accepting the laws of existence and working with them, we find ability and freedom. We don’t know if God creates each thing, but we do know a bit about how things are made and how they work.

To know how brief all of human history is, or how miniscule our entire solar system is, or how limited we are by space and time – is to see us a mere speck adrift in a meaningless universe. Perhaps the mind-bending scale of space and time in the scientific view of the world has us wanting the old, cozy view. It’s a bit lonely.

If a second equaled a year, it would take a half an hour to reach the time of Jesus, but three weeks to reach the first humans. At that rate it would take twenty years to reach the dawn of the Cambrian explosion when the trilobites lived. But this is only one ninth the time earth has existed. Stretch your arms apart to represent all of earth’s existence and the wrist of one hand marks the Cambrian explosion. All complex life exists in that one hand. All human history could be trimmed off a fingernail in one stroke.

It says in the Psalms that our lives are “threescore and ten, or by reason of strength fourscore.” Eighty years is a long time, plenty of time to gaze and wonder, to work and to love. Perhaps we could live another score of years to a hundred. Seems long until it’s gone. Our time frame is relative to us. On a cosmic scale, it’s either vast or inconsequential, depending on the vantage point.

To the bugs we must seem gods, but to the gods perhaps we’re bugs. Our importance seems upset also by scales of size. If earth were the size of a pea, Jupiter would be over a thousand feet away, and Pluto – a mile and a half distant, but it would be only one-fifty-thousandths of the way to our Oort cloud. Hard as it was to reach our moon, the next nearest star to us is a hundred million times farther. The stars in our own galaxy are so far away there’s no way we can plan to travel to them, or even communicate with them. We know they’re there, but we’re stuck here.

Here isn’t such a bad place. Our lifetimes aren’t too short. What a gift to be alive at all. Seems like we could think of some purpose.

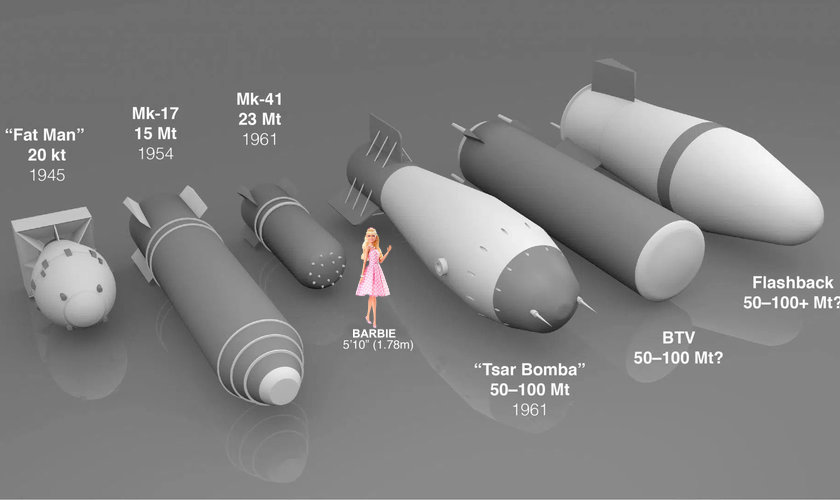

The dinosaurs lived here for sixty five million years. A nearly unnoticeable crater some 120 miles wide and (under the current soils of Mexico) some 30 miles deep marks the site of the impact of an asteroid coming in so fast the air in front of it grew ten times hotter than the surface of our sun. The KT impact sent so much soot into the air it blocked the sun, affecting our climate for 10,000 years. A Hiroshima-sized bomb for every person on earth would still be about a billion short of its collective magnitude. We’ve only recently discovered this. Though we have identified and mapped over 20,000 asteroids, there are a billion more.

Our own beautiful moon was knocked out of our earth by just such a collision. One moon is enough. We don’t need another.

Other natural mass extinctions have happened and are still possible. 74,000 years ago the Toba volcano led to six years of volcanic winter, narrowing the numbers of humans to only a few thousand for the next 20,000 years. Our own Mt. St. Helens exploded with the force of 500 Hiroshima-sized bombs, hurtling rock, ash, and hot gasses out at 650 miles per hour, enough to bury Manhattan under four hundred feet of material. But the last time our own Yellowstone blew, it was a thousand times greater than this, and before that it was some 2,500 to 8,000 times more explosive. Yellowstone is swelling again.

Earth has seen five major mass extinctions. In each case a few determined creatures lived on to start new lines of life. We are in the midst of the sixth extinction, except this one isn’t accidental, it’s somewhere between callous and inadvertent. We killed all the dodo birds because we could; they had no fear of us. North and South America lost about three quarters of its big animals when the hunter humans arrived. The beautiful emerald green Carolina parakeet is gone because it would fly back to check on the first one shot. Since the Stone Age, we’ve lost one species every four years on average, but recently the extinction rate may be 120,000 times that.

So, besides the natural threats of volcanoes and asteroids, besides the regular return of the ice ages, we have the human taunts to our reliable systems of life in the form of carbon dioxide emissions, ozone depletion, exotic pollutions, runaway bacteria and viruses, and our own propensity to war.

Our civilization is increasingly dependent on intelligent specialists. Who will maintain and further it if we teach faith instead of critical thinking? Put religion, western and eastern, in the midst of this, caring more for an afterlife or an instead-of-life, and you have humanity led astray. We are led to follow a fantasy formula of faith to fix a phony feeling of fall. We blunder into massive environmental dangers but are guided by sanctimony instead of practicality, responsibility, or even just plain common sense.

When President Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior was asked if the pro-industry policies would hurt future generations he smugly quipped, “I don’t think we have many generations left before the Lord returns.” An embarrassing oddity then, he was the avant garde of hordes believing in the holy inevitability of a grand conflagration at the Battle of Armageddon, from which believers will be magically carried away in the “rapture.” We have the bombs for this, and the myths, and the self-righteousness, and the people in power who believe it is inevitably part of God’s perfect plan. Is our choice between this sort of purpose and none?

The choice isn’t between purposelessness and a hideously stupid divine one. Perhaps the purpose of life is to give life purpose. If the only thing we inherited from the long, demanding process of natural selection was the drive to pass on our genes successfully, that would be some purpose. After all, every one of our ancestors, human and pre-human, did that in their life times. Each successful adaptation accumulates upward into increasingly complex and capable organisms. They lived long enough to pass on the next generation. They didn’t quit, fail, or commit suicide. There are no failures built into us. We inherit and are the structure of success.

The least we should do is survive. We could act so as to assure the seventh generation out from us will have the wherewithal to survive. To do this, we must heed the important environmentalist word – sustainable. It is near akin to that important word in Genesis One – replenish. Are we replenishing and sustaining our soils, our sources of fresh water, our oceans, our energy needs, our humane impulses, our human rights, and our science?

The astronomer Harlow Shapley once noted how much progress humankind has made since the recent rise of science a mere four hundred years ago, and he asked how much more we could do if we were to survive another four hundred years, or another four thousand years, or another four million years.

In efforts to know the purpose of life we have listened to those who would divide us from life, sacrificing all life and our time in it on the gamble that it doesn’t matter as much as their supernatural scheme and the list of goods and evils they claim to know with authority. There is a division between good and evil, but it is between what God called “good” and their fallen versions of good and evil. What is good is what Elohim God is said to have said it was: sunlight, water, earth, plants, fishes, animals, and humans, males and females. If you would honor the Creator, cherish this good creation. If you don’t believe in a Creator, cherish this good creation.

Even if we live fourscore years, they are as the Psalmist says, “soon gone and we fly away.” He or she then went on, “So teach us to number our days that we might get a heart of wisdom.”

The purpose of life could be to love life. Are our soils growing? Is our water used well? Do we ride this blue ball beauty enjoying and protecting its glorious garden? Do we respect, protect, and allow other creatures and life-forms to flourish? Do we help raise our fellow humans up into their dignity and foster their creativity? Do we honor whatever Creator may be, from divine to all the forces and ancestors we inherit, by living well in Creation while caring for it? Do we deepen our beings by being able to be silent, compassionate, and soulful? Do we celebrate our bodies and pray “Yes!” to our Creator? Do we sing? Do we care?

Yes, we care. We sing. We think. We know. We question. We try. We teach. We learn. We mend. We wonder. We love. We fall. We rise to our own precious, precarious, fallible, able selves, alive as best we can be in an endlessly marvelous and precious creation. Far from offending creation, this would fulfill our part in it. We rise to know our reality and dare to love it.

Reverend Brad Carrier

For the Unitarian Universalists of Grants Pass

Grants Pass, Oregon

C March 20, 2005

Subscribe

0 Comments