How we view our history and future can be skewed, or even screwed if we don't see either well. I promised my readers I would…

Autobiography of the Founder of God’s Goods

Who am I to found a religion catering to atheists, ecologists, libertines, humanists and believers? Read on.

I’m not one to feign piety or push fantastic beliefs. Those who do – annoy me. I’m largely humanistic (humans are free, fallible, and able), naturalistic (nature is dear; it is our origin and home), and deistic (the divine is found more through nature than scripture).

God isn’t the mean inscrutable man most of the theistic religions believe in and brandish; God is the answer to What Is that we know must be, yet is beyond us. We don’t create the universe, except as we attempt to perceive, label and use it. Rather, it creates us, allowing our speculation, investigation, and potential mastery. How it does and why I call God. That some revere this, or detest it, or serve it, or forget it – doesn’t primarily concern me. Any God worthy of belief wouldn’t demand it.

The point of God’s Goods isn’t God; it is what is good and how to relate well to it. Studying the reality of nature itself and consciousness itself unveils God. Scriptures and religious authorities might lead us to God, or they might lead us to silly exaggerations and destructive delusions. Science and mysticism make more religious sense to me than do the Bible or the Pope. We love whatever Creator there is by serving Creation. Or we love and serve Creation itself, in and of itself. Relating well to our precious reality, physical and spiritual, is the prophecy I promote.

Prophecy doesn’t profit the prophet. People don’t like hearing sensible “if-then” relationships, so they try to ridicule and ignore the prophet. But in the larger economy and ecology of human involvement, prophecy is needed. My approach, grateful for the larger cosmos that generates life and allows us to evolve, is critical of most religions, and seeks better relationships among humans, with life, reality, and “God.”

Though prophecy usually doesn’t pay, I choose to devote my life to it, trusting a decent living in return.

For me, this calling to prophesy came not a single blinding flash, but an accumulation of realizations and inclinations gathered over a lifetime. At age 78, it is time to deliver these over in service of God’s goods. Here’s what led to my founding God’s Goods and its website, earthlyreligion.org.

_____________________________________________

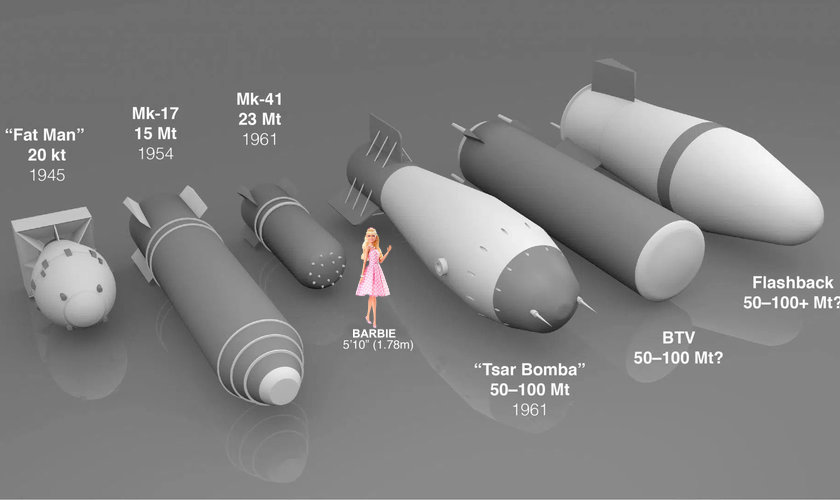

I was born the day my country bombed and burnt to death hundreds of thousands of mostly innocent civilians in Hiroshima, Japan. Reasons and rationalizations notwithstanding, the plain fact is we showed our will to kill civilians. Talk about terrorism!

Any desperate or deluded person or group can do that. Humanity can’t go back to simpler weapons. Whenever there is a better shield, a better sword will be built, and then a better shield. What can protect against huge bombs or tiny viruses? Military answers must and will be given, but what of spiritual and social causes and their corollary answers?

This seems a background theme of my life – the ridiculous yet typical propensity to create, and then rationalize, the needless violence and waste of war. In Iraq (which never attacked us) today [originally written in 2004] my government has killed more innocents than we lost when others attacked our Trade Towers and Pentagon. It is a mad rush of wasting energy to seize energy in order to go on wasting energy in our fat cars and sloppy technologies. We accuse them of having the weapons we use. They hate in vengeful reprisal. We thus mutually assure ongoing cycles of vengeful reprisal.

As a boy of seven or eight, I remember the happiness of the ending of the Korean War. My dad was a product-testing engineer at the Cadillac Tank Plant in Cleveland, Ohio. My mom joked about being stuck in the top hatch of one because she was pregnant.  Dad painted the testing of the new hydrogen bomb at Bikini over our mantle, the huge explosion flipping mere battleships. Mom’s sweet potato plant framed it with green leaves. Mom was probably embarrassed.

Dad painted the testing of the new hydrogen bomb at Bikini over our mantle, the huge explosion flipping mere battleships. Mom’s sweet potato plant framed it with green leaves. Mom was probably embarrassed.

I drew early pictures of tanks and guns. I thought the nazi swastika was cool looking until I realized they were the bad guys, who I should hate. Later, in high school in Michigan, I was halfway through All Quiet on the Western Front before I realized a German wrote it. My sense of “us and them” had to get switched, even though my sense of humanity for them and us was touched. We are “them” to others, though we are all inextricably “us.”

Two other budding trends had started by then on Oakland Lake in southeastern Michigan.

One was the gradual awareness of the loss of life in the lake. When we got there muskrats built mounds in the lake and tunnels on the shore. I helped trap them, catching their legs below the ice so they’d drown, and I could skin them and get a dollar at the hardware store.  Huge dogfish swam below their brood. I’d spear them through the babies, but then not eat them, for they were in a class with catfish, said to be not edible.

Huge dogfish swam below their brood. I’d spear them through the babies, but then not eat them, for they were in a class with catfish, said to be not edible.  We even had ancient garpike out in the middle of the deep lake, huge alligator snouts.

We even had ancient garpike out in the middle of the deep lake, huge alligator snouts.  All of these animals disappeared from the lake, eliminated by boys like me and all the lawn fertilizer and oils polluting the ecology of the lake. Regret for what was lost began to enter me.

All of these animals disappeared from the lake, eliminated by boys like me and all the lawn fertilizer and oils polluting the ecology of the lake. Regret for what was lost began to enter me.

My dad didn’t hunt, but I wanted to “be a man,” so I asked the man across the street if I could go hunting with him. He said he would take me, but first I had to practice by killing the blue jays that woke him in the mornings. I’d sit under his trees, BB gun in hand, waiting. When I did shoot a jay it lay there on the ground, glaring at me, as if to say, “Why?” I had to shoot it again and again. Still, it didn’t die, so I threw it against the tree till it did.

I also used to flush pheasants with my Irish setter as an excuse to walk in the fields, and then we’d hunt them during the season. I used a single-shot 20-gauge shotgun. It was more sporting than a 12-gauge repeater.

But the same thing happened. I’d down a bird only to have it stare at me till I reached in and broke its neck. The few bites of meat didn’t justify the unease I felt at killing the beautiful bird.

I began to realize being a man meant being callous enough to kill even if my heart was against it. Realizing that, I then renounced hunting. I’d rather let the animals have their lives. Killing them violated them and me. I renounced what was not me and so became more myself. This would not fit with other boys and men, but to be an honest man I had to admit my repugnance at killing even simple creatures.

The other realization came in composting. The old German couple that lived next to us would put their table scraps in an ongoing trench in their garden, changing what would be garbage into soil. I experimented with it, putting coffee grounds in a place near the shore, soon finding many more worms there.

I also began experimenting with how many sheets of toilet paper it really took to get the job done. It seemed wasteful of my parent’s money and the paper itself to use more than needed. I went from eight to six to four. I used less than half of what I once did. Could such a small, simple, and private thing influence the world? Only years later, reading Buckminster Fuller and Fritz Schumacher, did I realize it could and does. What even one does matters, especially when millions of other ones are doing it too.

I was the oldest of five children. Dad was twenty years older than Mom. She, being Catholic, didn’t allow any sort of birth control. Five was a lot. Dad, who once told me everything a man does is to have a bed to sleep in and a woman to share it with, slept in the basement, alone. Ironic, eh?

Though raised Catholic I began to question it. At age fifteen I went to the nice priest in his office (not the screened confessional) to confess I didn’t believe in the Catholic teachings on birth control and other religious teachings, so continuing to come was the sin of hypocrisy. I had liked the aesthetics and short sermon of the Mass and valued some aspects of the religion, but couldn’t go on pretending I believed when I didn’t. I left. This caused upheaval in my family.

In my senior year in high school, I stumbled into a Methodist weekend seminar called The Ecumenical Institute. They wore us down with a recounting of the twentieth century, asking at the end, “Who are you and how do you fit into this?” Am I just a student, just a consumer, or do I have some responsibility to the world?

I had taken a job at the local funeral home, doing their yard and parking cars at funerals. Then I helped move caskets and get bodies from the hospital. Then I helped in the ambulance. (Funeral homes supplied ambulance services then, using their large hearse for a makeshift ambulance.)

I saw people die, saved a few from it, and caught a baby when the mother delivered it. I helped embalm bodies, even some of the people I knew, back from Vietnam.

The decent owners of the funeral home urged me to get a license, so I did. Though I had studied art mostly in high school and had no plans for college, I had to do two years before going to mortuary school. While I had avoided all science earlier I fell in love with it in junior college, especially chemistry and anatomy. The reliable marvels of the actual structure of matter and life amazed and intrigued me. I liked college-level learning so much that I returned after mortuary school to work on a bachelor’s degree.

By then I had started attending a Unitarian church, attracted by a sermon about sex on Mother’s Day. Thoughtful sermons were the center of the Sunday service. Unitarians welcome and practice philosophical and social inquiry, honoring reasonable investigation and skepticism of religious claims. By the time I graduated (with honors in psychology and philosophy), I decided to leave funeral directing and become a Unitarian minister. Funeral directing can be a decent profession and was where I worked, but it was rarified, dwelling always on bodies and grief. I wanted to take on the larger life that includes death while transcending it.

The seminary was very dynamic during those revolutionary years. The school (Meadville Lombard Theological School), supposedly liberal, was really fairly stuffy, though it was located at the famous University of Chicago.  Mircea Eliade, founder of the History of Religions, had his office in our seminary. (The Unitarians once held all four corners of 57th and Woodlawn. Now they’re down to one.)

Mircea Eliade, founder of the History of Religions, had his office in our seminary. (The Unitarians once held all four corners of 57th and Woodlawn. Now they’re down to one.)

Two ideas especially enthused me then, Jungian psychology and Eastern religions. When I got to the University of Chicago in 1969 I met a man from India who was fresh there from having studied with Carl Jung. Dr. Vasavada became my close friend and teacher.

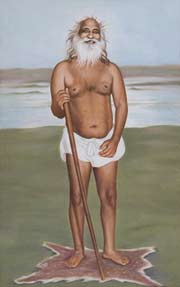

Until I taught him to drive, I would drive him around. (I taught him to drive a car; he taught me to drive in life.) We’d talk of meditation and his gurus. I’d sit with him at his Friday evening group meditations. After, we’d share tea or scotch. I went with him to meet his guru, the Blind Saint of Brindivan, Swami Sharnanand. (See “Gurus,” posted elsewhere at this site.

I had two questions for the saint. The first embarrassed the translators, but not him: “What is it like to be a saint; how does it differ from what I have?” “A saint is a member of the universal human family,” he laughed. Bronze skinned, his vacant eyes would roll down from up in his head as if looking at me.

I had two questions for the saint. The first embarrassed the translators, but not him: “What is it like to be a saint; how does it differ from what I have?” “A saint is a member of the universal human family,” he laughed. Bronze skinned, his vacant eyes would roll down from up in his head as if looking at me.

The second question took more answer. “I am appalled at the violence of my country in Vietnam,” I complained, “what can I do to change it?” “What is the cause of war?” he asked, and answered, “It is men taking fascination with their minds and the products of their minds,” an unexpected reply. He went on to say any effort at changing these results only in limited and sometimes opposite effects, because of being in the realm of cause and effect. He held my hands, feeling them. “What do you do?” he asked. I tried to explain my learning and Unitarian ministry. He said to give up my books and devote myself to hard physical labor for the general betterment of mankind, not asking for pay, but taking whatever is offered. “Then,” he went on, “when you are tired you will find peace, and you will emanate an invisible perfume of unlimited effect.” That perfume would create deep, unreactive peace.

His answer, perhaps a stock one, has lived in the back of my mind ever since. It comes true, I find lately when I work hard at building dry-stack retaining walls out of boulders, rocks, and crushed rock. I make them as aesthetically beautiful as they are structurally sound. It is a meditation in the Now, taking lots of physical work. I sweat and toil. Each rock has its own challenge and reward. Each rock shares the load with the others. At the end of the day, my work has lasting results, lasting for hundreds of years. When I shower, it’s worth it, the dirt flowing down the drain, gone. My meditations or sleep are indeed deep. Maybe the perfume of unlimited effect emanates. Seems so.

Of the many other events and lessons in India (the large wild monkey herd at the Ellora Caves, the wild eyes of the Jain gods on the top of Mount Abu, the mix of peacocks and flies, or saints and thieves) two stand out.

One was looking into the eyes of the last remaining wild Asian lions in the western preserve in Gudjrat State. Moslem cattle ranchers are driving these beautiful beasts into extinction. They epitomize the loss of life rampant in the world, like what I helped do at Lake Oakland. The rivers in India bubble from the fermentation of all the feces in them; they are used as sewers, wasting that resource. (The sacred cows, ridiculed in the West for being a silly waste that could be killed and eaten, are actually an ecologically sensible tool. They wander all day, eating the mango rinds and other table scraps of the village, pooping fuel as they go, returning at night to be milked, which is turned into yogurt. They clean the village and provide ongoing food and fuel.)

The other was meeting Sri Rajneesh. I had gotten horribly sick. I avoided nothing in India, thinking my resilient body would ward off any pathogens, not realizing even the Indians get dysentery. I went from a slim 145 pounds to a wasted 125. I discovered just how full of shit I was! I also had been robbed, so was grateful to be housed at a relative of Dr. Vasavada’s near the Parsi Towers of Silence (where they leave their dead to be eaten by vultures) section of Bombay. (Vasavada and I never traveled together as planned because of a death in his family.) I saw a poster for a notorious guru, Rajneesh. India may have once had a sexual culture,  as depicted in the erotic statues on some of their temples, but is today a puritanical culture with a clear separation of the sexes. Rajneesh, of the Tantric tradition, was said to encourage sexual wildness as a way of getting past that fascination.

as depicted in the erotic statues on some of their temples, but is today a puritanical culture with a clear separation of the sexes. Rajneesh, of the Tantric tradition, was said to encourage sexual wildness as a way of getting past that fascination.

When Rajneesh entered the posh hotel room all his devotees glowed with adulation. He wore clean whites and sported a Rolex on his wrist and a big ring on his finger. He had incredibly beautiful eyes, very calm and present.

He went on about the very thing I found difficult in Indian religion – that we are not the body and this world is just Maya, an illusion. I thought of how this plays into the Indians allowing their rivers to turn to cess. I thought of how sick I was. I thought of the square block of cardboard “houses,” only a few miles from where we sat, where a thousand people shared one water spicket and no toilet. Here he sat in privileged ease, knocking the communists for caring about earthly conditions, claiming realization is worth the abandonment of our mere earthly Maya. I thought all this and wanted to go up and smash him hard in the nose in order to ask him a philosophical question: “If the body is not real and the world is just Maya, would you mind if I hit you again?”

I didn’t, for I didn’t dislike him or want to actually hurt him (and then get me jumped by his devotees). But I saw in his smug stance a dismissive, uncaring attitude towards the very real suffering in India.

I saw the Eastern belief in Maya (favoring some other realm than this embodied, earthly one) as the counterpart of the Western belief in an afterlife (favoring the soul’s lasting abode in heaven or hell over the mere temporary drama of our lifetimes). Neither takes the precious possibility of a lovely, sustainable life here on earth seriously or responsibly. Both substitute far-fetched speculations and egoistic posturing for an ethical and rewarding life here on earth. Both sin this way. The people of both cultures who look for identity and reasons to do what’s right are religiously misled.

I returned from India to an even greater culture shock – the shallow life of frantic and wasteful consumerism. Having seen the value of clean water when thirsty, or a banana when hungry, to see the rampant waste of our glut serving no higher purpose – dismayed me.

Skinny, and broken down in spirit, I went west to southern Oregon and lived in a sort of commune with some hippies in the woods. Oregon was so much more awesome in turns of ample nature than I had known in Michigan. The trees formed an overstory under which one can roam easily. Elevation is all in turns of weather. The salmon still come up the streams. The culture is young, not settled into family dynasties and set cultural assumptions.

With the hippies and other “counter-culture” types, I came to experience and value all those things we’re now told we’re to be beyond: sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll. I affirm them. Prissy, picky preachers never appealed to me. I am a whole human. I don’t want to sell my soul by pretending to be pious. I’m with Emerson on this – authenticity trumps posturing.

As a Unitarian Universalist minister for fifty years now I have praised sex from the pulpit, though not as fervently as I could and it deserves. I am libertine towards it. While it can be a realm of obsession, addiction, and ample troubles, it can also be a realm of great pleasure, soul communion, and life satisfaction. The drive to think about sex ought not be denied or shamed, but welcomed, investigated, and shared. It is matched only by the other human propensity towards it: shame. I’m against the shame, religiously, though I admit many cling to it religiously.

As earlier in seminary, so then with the hippies, and even now, I found certain types of drugs to be worth the risk. Pot, LSD, mushrooms, mescaline, peyote, Ecstasy, and especially 5MeO DMT open the inner paths to realization and awed, loving connection. Being anti-addictive (though pot can be an over-used habit) they stand in the opposite corner from the problematic addictive drugs: speed (meth), cocaine (crack), and heroin. I never cared for the latter group. I never gave into the social demand to condemn, deny, and prosecute the former. Such drugs are part of our human curiosity and rights. All cultures have some sort of intoxicants or entheogens. The issue for me (other than speaking against ignorant and counterproductive repression of them) is which do what and so which to favor or not. Some are nothing short of entheogens (to put/find God within); they are sacraments with results. Being able to use them is our religious right.

Finally, rock ‘n roll sums up any and all human enjoyment of music. Humans make and enjoy music in a way the other animals don’t seem to. While the birds, frogs, etc., make their music, ours is far more varied and prone to make us dance. When a tune resides in my mind overnight, it intrigues and delights me.

Besides this trio, I also came to value and promote an earlier theme from my life: ecology. How can our culture claim to be advanced if there are fewer salmon in the streams than when we arrived? What technological blunders enamor us to our peril? How are we being responsible if the aquifers are drained or polluted? Should we hurry to waste all our oil despite global warming? Do the trees, which shade the ground and transpirate water, cool the air, and thus attract more rain deserve our protection? The shared systems of our massive yet fragile earth could live in splendid abundance for millions of years, were we to treat them right. My early care for fish, birds, compost, and using less toilet paper was part of a collective consciousness that can not be a mere fad – if we are to survive.

Healed from India, I returned to the Midwest and took a job as a campus minister in Urbana, Illinois. There I found, while reading a Catholic bible, the most amazing scripture passage: Genesis One.

Genesis One forms the scriptural foundation for God’s Goods. Though I don’t claim the bible is the “word of God,” I favor this passage for what it says God says: this universe, our earth, all life, and we humans too – are all good. These are the six stages of the creation story, remarkably close to the scientific stages of physical and biological evolution theory. Significantly, each and every stage is not only created by God but is valued by God as “good.” Humans (males and females) are part of this, which God values as good. To me, this passage justifies naturalism, humanism, and deism. To the rest of the religious world, so bent on instilling shame and alienation, it stands as a beacon and challenge.

I began preaching on this back then. The God of this passage is very different than the God of the Garden of Eden passage, the second creation story. That God is singular and masculine, YHWH. This God of Genesis One is singular and plural, masculine and feminine, Elohim. While Genesis Two and Three describe a change in consciousness, losing the goodness just described, chapter one reminds us of the given goodness of natural existence and suggests a way for us to be in it.

Another thinker was working on the same basis: Matthew Fox, who wrote Original Blessing. I found in his book agreement with my emerging realization of what our world needs religiously.

I worked half-time as the minister of the Channing/Murray Foundation, located on the campus of the University of Illinois in Urbana. Dr. Vasavada married Janice Lynn and myself, and we had our first son, Tobias Iam. We left to investigate Costa Rica, but returned to Florida, then to North Carolina, where I took a job as a country preacher for an old Universalist congregation, where I served for five years and our second son, Ira Abraham, was born.

Doing UU ministry but not having finished seminary or received the denomination’s fellowshipping (I had been ordained in 1973 by a church in Michigan) we returned to Chicago where I received my Master’s of Divinity. I received fellowshipping two days after our third son, Benjamin Byron, was born (also at home, as had Ira).

Doing UU ministry but not having finished seminary or received the denomination’s fellowshipping (I had been ordained in 1973 by a church in Michigan) we returned to Chicago where I received my Master’s of Divinity. I received fellowshipping two days after our third son, Benjamin Byron, was born (also at home, as had Ira).

It was during this interval that I also started a three-year stint of graduate-level training in humanism at the Humanist Institute in New York City. (If ever I raise money for organizations beyond my own, this would be one of them.) This valuable storehouse of rational thought impressed me, even if it was also not very aesthetic or emotional. It is the sort of thought ridiculed by conservative Christians. It is humanity’s treasure, a valid part of any sensible and responsible religion. Unfortunately, it is largely at war with God and religion (for all the silly, sad, and diverting aspects of those). Rationalism, criticism, and skepticism are needed, but so is heartfelt religious coherence. Can humanism exist with God? To me, humanism is an aspect of the fulfillment of the goods God generated.

It was about this time when I also had the opportunity to meet Mr. Nobody, Sri Shunyat, at Vasavada’s.

Shunyata is in the line of awakened mystics through Ramana Maharshi. We liked each other and we conversed by mail for some years after that. Rational and scientific though I am and favor, I also am drawn to the inexplicable lure of the gurus, not for show or position, but because of something inner. I see this as fulfilling humanism in a way most humanists would not.

After a hellish year in Charlotte, North Carolina, I was assigned to be the first minister for the thirty-year-old fellowship in Ashland, Oregon, just miles from where I had earlier lived. I was to help them grow. Grow we did, tripling the congregation in a few years and buying their first church building. I had a knack for preaching and being with people. I adopted a decidedly liberal public stance in an era when that word was being ridiculed and sidelined. I also helped start a fellowship in neighboring Grants Pass and often visited others in Oregon and California.

Success was stress. Upon occupying our new lovely building I found my creative urgings ignored. I felt isolated in the midst of the public eye, lonely for company and touch, which I wasn’t able to enjoy at home. When I started to get close to a young woman marginally related to the congregation (but stopped) it still became a huge issue. Though I answered it all honestly then (President Clinton squirmed out of his predicament by asserting, “It depends on what is is.”), there was too much accusation and divisiveness, so I resigned at the end of my eighth year. Though over half of the congregation supported me and wrote the denominational officials in defense of me, only to be ignored while they advised the board otherwise, the wear and stress proved too much. I found no support, no comity from my colleagues and denomination after that.

Having moved to ten houses by the time I had entered the fifth grade as a boy I didn’t want to jack my boys around the country in equally ephemeral ministerial settlements. I made a go of it in Ashland doing wage work, mostly picking or stacking rocks into retaining walls and steps.  I liked this hard physical work, which reminded me of Swami’s suggestion regarding labor. After a couple of years, I became an independent contractor, then later an employer, all in this unexpected realm. I also continued to serve small Unitarian fellowships on weekend visits and write infrequent editorials.

I liked this hard physical work, which reminded me of Swami’s suggestion regarding labor. After a couple of years, I became an independent contractor, then later an employer, all in this unexpected realm. I also continued to serve small Unitarian fellowships on weekend visits and write infrequent editorials.

But in the back of my mind during ministry and after was always this urge to explore and share my earlier inspiration related to Genesis One. The question from the Ecumenical Institute was still apt: where do I place myself in history? We are the incarnate generation. Who will rescue the world from its misdirection? If not me, then who? If not now, then when? How could the world’s great problem religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) forget and forsake the clear message of Genesis One? It’s as if they play the role of the subtle deceiver snake, tricking us into a false or confused sense of good and evil, alienating us from the original and ongoing goods that underlie and beckon us.

How is it the world’s three great monotheistic religions dwell on the problems of Genesis Two and Three, shaming people for their sexuality, excusing ecological and economic ruin, blasting evolution, and waging wasteful wars, while overlooking and ignoring this single scripture passage underlying all their scriptures affirming the natural and human order as good?

For decades this message has been calling me to share it. Hence, I yield to this ongoing intuition to work in this realm, sharing and challenging both secular people and religious types to admit the words of Genesis One and to apply them to this, our given, obvious, and precious realm.

The words of Genesis One don’t create value. The goodness of the world (and us in it) precedes and transcends any words or scripture. It just happens that this scripture, so foundational in the world of religion, also affirms the natural order and our human freedoms and responsibilities in it.

I wish to devote my time, talent, and learning to this message. I don’t know where it will lead. It will unfold. There is an inexplicable blessing assisting. I am no saint. I found this religion on my (and everyone’s) fallibility and ability. I hope to spend time doing commentary, ceremonies, and counseling. I can stack rocks, and like to give my labor to that which betters a place, but my work should be more deliberate and productive now. I want to make a decent profit doing prophecy, helping save the world as I go through it and out of it.

Hopefully, I will use such income to secure a happy life with my darling.

Maya and I enjoyed seven years of togetherness even though we were usually a thousand miles apart. (Literally; she lived in L.A. and western North Carolina, both distant from me.) Our one-month-per-year monogamous relationship finally grew apart.

Now, well into retirement, I try to be of some benefit and consequence in my local and larger world. My former wife has died. My boys have become men. My relations with the UU world fell apart. (See “Emeritus,” “Endings,” and “More Endings” at this site for that story.

I still have that Emersonian habit of being a seer and a sayer. I try to participate online with various communities. I volunteered for a local environmental group and another one promoting electric vehicles (because they’re environmentally superior).

At the constant edge of poverty (my having left funeral directing and not pursued a more lucrative UU ministry) I recently managed to purchase an eleven-year-old Mitsubishi MiEV with half-shot batteries. It has enough range to get me around town far safer and more comfortable than the electric bike I had used for three years.

My trusty A2B Electric Bike

My cute, comfortable, and environmentally clean Mitsubishi MiEV

Estranged from the UU ministry, I may take more training in psychology and counseling, perhaps as part of Oregon’s new psilocybin program. But both are expensive and I’m still in get-by mode. So I write here and tend to those in my circle who may need something. At age 78 I’ve had my health scares and accidents, but, as they say, “By the grace of God,” I’m very healthy and glad to be alive. My fun in singing karaoke (see “Singing My Way” at this site) music on the electric guitar and piano, and both savoring and sharing the life I have left.

If you’ve read this far I hope you’ll read my other sermons and editorials and help support my work, my dharma. Vasavada said dharma is our inner nature wanting to do its work. Jean Houston and Neale Donald Walsch call it the Soul, calling. This is mine.

Byron Bradley Carrier

August, 2004, updated 2012, updated 2016, updated 2023.

Subscribe

0 Comments